Getting to the Root of the Meat Debate: The Agreements We Must First Make

Before we can have an honest conversation about meat—about whether humans should eat it, about whether it is ethical or sustainable—we need to establish a foundation. If we cannot agree on certain fundamental truths, then the discussion is not worth having.

This is not a debate where facts alone will suffice, because facts, without shared principles, are meaningless. Just as a conversation about abortion or capital punishment is fruitless if we do not first agree on whether human life is sacred, so too is the meat debate meaningless if we do not first agree on the nature of life itself.

So here are two core truths. If we cannot see eye to eye on these, there is no point in proceeding further.

First Agreement: The Current System Is a Crime Against Nature

Let us start here.

If you do not recognize that modern industrial animal farming—concentrated feedlots, monoculture grain production for livestock, the unnatural diets and conditions of factory-farmed animals—is a perversion of nature, then we have no common ground.

To raise animals in cages, force-feed them food they were never meant to eat, pump them full of antibiotics to keep them alive in conditions that would otherwise kill them, and then dispose of their waste as pollution rather than as a vital part of the fertility cycle—this is an abomination.

It is not just unethical; it is anti-life.

If we can agree on this, we can move forward.

Second Agreement: Life Is an Energy Cycle, Not a Linear Process

The universe began as pure energy. Over time, energy became matter—atoms, then stars, then planets.

For eons, Earth was nothing but rock and sun, locked in a cosmic dance, much like electrons orbiting a nucleus. Then, something miraculous happened.

Life emerged.

And life, at its core, is an ever-expanding process of capturing, storing, and recycling energy. Plants learned to harvest sunlight. They transformed that energy into sugars, fibers, and structures. They pulled water from the sky and minerals from the earth. And then, animals entered the equation—not as mere consumers, but as vital participants in this cycle.

The more energy captured and stored in ecosystems, the more life flourished. This is not a zero-sum game—it is a self-reinforcing process, a regenerative spiral.

And animals play a critical role in this.

The Role of Animals in Regeneration

Herbivores are not parasites on the land. They are essential to its fertility.

When they graze, they do more than eat. They prune vegetation, making room for new growth. They digest minerals locked in plants and return them to the soil in a usable form. They aerate the land with their hooves, break up compacted earth, and spread seeds across vast landscapes.

But left unchecked, herbivores would strip the land bare. This is why carnivores exist—not just to maintain population control, but to shape behavior.

Predators force herbivores to move. In doing so, they prevent overgrazing, ensure that plants have time to recover, and maintain the balance of the ecosystem. Herbivores, fearing predation, avoid riparian zones—those fertile areas near rivers—because staying there would make them easy targets. This prevents erosion and protects the most vital areas of the landscape.

And after the carnivores have fed, the omnivores arrive—birds, wild pigs, and scavengers. They break down manure, consume insects, and aerate the soil, creating yet another layer of fertility.

This is how nature works. Not as a series of independent actors, but as an interconnected whole.

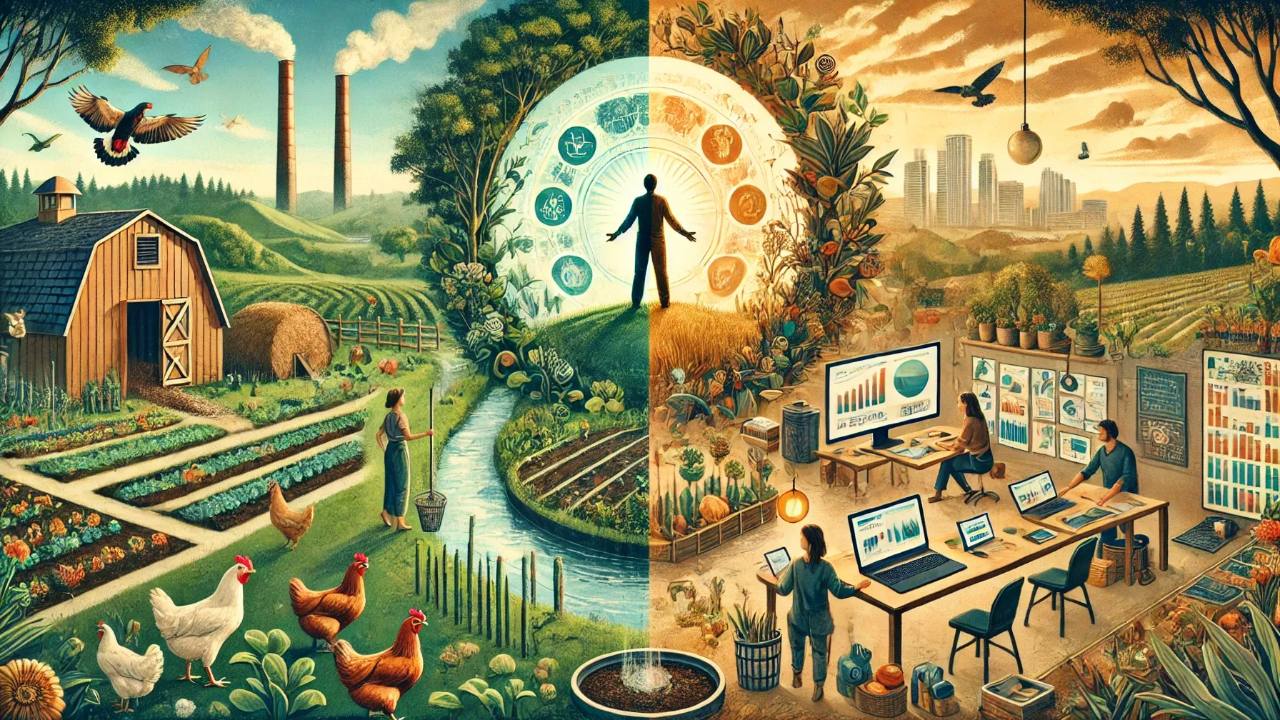

What This Means for Farming

A farmer who understands this system does not see animals as separate from the land, nor does he see them as a necessary evil. Instead, he sees them as the key to abundance.

By maximizing sunlight capture—by growing more grasses, trees, and plants—he increases the amount of energy available. This fuels more insect life, which in turn supports more omnivores (chickens, ducks and pigs), which in turn supports the entire food web.

Furthermore, managing animals in this way means that we now have an abundant supply of compost, which allows us to grow all of the plants we need for a balanced diet in a sustainable way.

When done correctly, this does not degrade the land. It restores it.

And this is why the common argument against meat—that growing food to feed animals is a waste of resources— is simply missing the point.

Animals, when raised as part of an ecological system, do not compete with humans for food. They create food. They turn otherwise unusable land into fertile ground. They regenerate soils, sequester carbon, and increase the productivity of entire landscapes.

The real crisis is not meat itself. It is the industrial mindset that views food as an input-output equation rather than as a living process.

The Final Affirmation

So the real question is not "Should we eat meat?"

The real question is:

Will we align ourselves with the patterns of nature, or will we continue to impose a mechanistic, reductionist worldview onto a living world?

If we choose the former, we have the opportunity to create abundance—an agriculture that heals rather than destroys, that enriches rather than extracts.

If we choose the latter, we will continue the cycle of degradation, loss, and scarcity that has defined industrial civilization.

The future of food, and perhaps of life itself, depends on our answer.